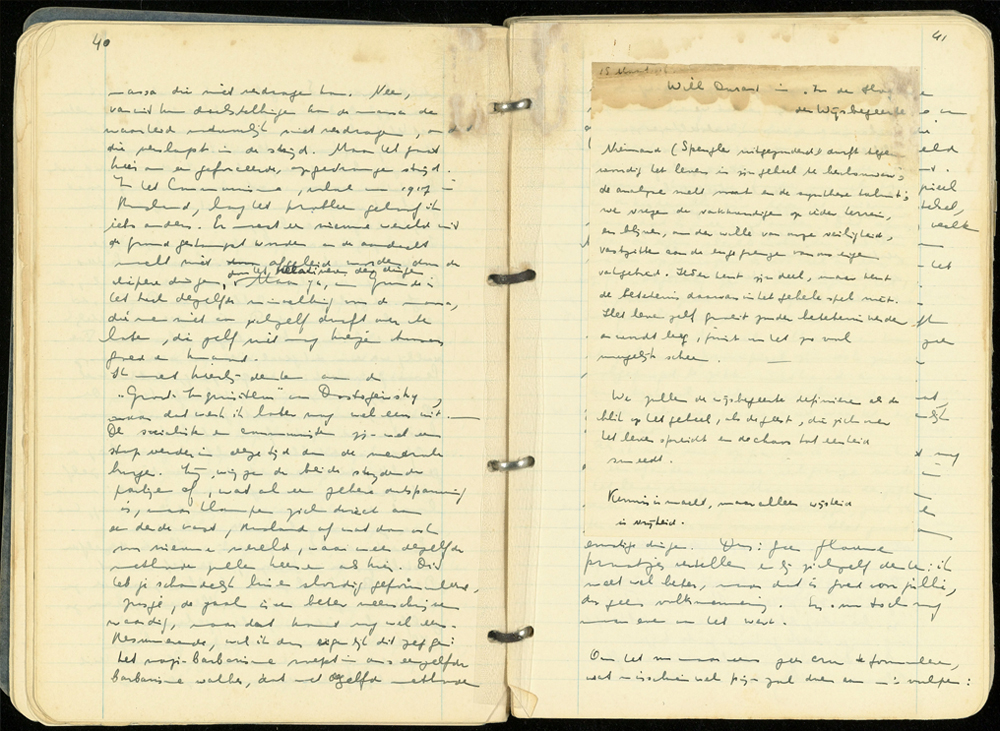

In 1941 and 1942, Etty Hillesum kept a diary in Amsterdam. She did this on the advice of her therapist, psychochirologist (that is, a palm reader) Julius Spier as a form of therapy. For her, however, writing in these diaries was not only a matter of psychological hygiene, but also a way of practicing her writing skills in order to become a writer. She aspired to become the chonicler of her time. In her diaries and letters, she tried to depict as accurately as possible what was happening in front of her. However, she must have known that her chances of fulfilling this dream were remote. She had no illusions about how things would develop when she was deported to Poland. Therefore, she tried to keep her writings from disappearing with her at the same time in two ways:

First, she wrote two letters about the conditions in Westerbork, the first in December 1942, the second on 24th August 1943. Those letters came to Petra (Pim) Eldering and through her to David Koning. He disguised the identity of the writer of the two letters. In an introduction to their publication, he described the life of a fictitious painter he called Van der Pluym. In addition, he added a third letter, which he had written himself. In this way, in 1943, an illicit publication of two of Hillesum's letters appeared under the title "Three letters of the painter Johannes Baptiste van der Pluym (1843-1912)". Although the name Westerbork does not appear in this booklet, it was readily apparent to the reader to which camp these two letters were referring. Secondly, Etty Hillesum entrusted her Amsterdam diaries to her roommate Maria Tuinzing before she finally left for Westerbork on 6th June 1943. She instructed her to hand the notebooks to the writer Klaas Smelik, should she not return. He had the responsibility for publication. Etty Hillesum had met Smelik in the mid-1930s, and she assumed that as a writer he would know how to find the right channels to enable publication of her writing.

After the war, when it became apparent Etty Hillesum had not survived the atrocities of Auschwitz, Maria Tuinzing contacted Klaas Smelik and presented him with the diaries and a small bundle of letters. Smelik’s eldest daughter Johanna (called Jopie in the diaries), transcribed parts of the manuscript. She was able to decipher her friend’s often illegible handwriting. Throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s, Klaas Smelik offered the manuscript to various publishers. Time after time, the text his daughter had so carefully typed was returned with a polite refusal. The diaries were deemed to be too philosophical. The two letters that were illegally published during the war were republished. They first appeared in 1959 in the magazine ‘Maatstaf’. Later, they were published as a stand-alone publication. The re-release was not successful, and many copies were remaindered. The public was not yet ready for the philosophical thoughts and ideas in Etty’s writings.

In 1979, however, things were different. Klaas A.D. Smelik, the son of Klaas Smelik, saw it as his task to ensure publication of the diaries. He received the diaries from his father and contacted the Haarlem publisher, Jan Geurt Gaarlandt who showed interest. He had those manuscripts, not already typed up by Johanna Smelik, transcribed by volunteers who, unfortunately, had difficulty reading the handwriting, resulting in quite a few errors. Based on this text, Gaarlandt compiled a selection from the diaries, especially from the last notebooks. He added some of Etty Hillesum's letters and wrote an introduction. He chose 'An Interrupted Life' as the title.

On 1st October 1981, 'Het Verstoorde Leven' was launched in the foyer of the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. Many friends of Etty Hillesum attended this gathering. Times had changed. Now, there was great interest in what Etty Hillesum had written during the war. One reprint followed another and, at the time of writing, there have been twenty-six. Translations appeared and continue to appear all over the world. After 'An Interrupted Life', Gaarlandt published a volume of the letters Etty Hillesum wrote in the Westerbork camp, under the title ‘The Thinking Heart of the Barracks’ (1982). This edition has also been reprinted many times and published in various translations. Meanwhile, Johanna Smelik discovered the sixth diary notebook (the seventh is unfortunately still missing). Gaarlandt decided to publish most of the contents of this notebook separately under the title ‘In a thousand sweet arms’ (1984), not knowing that this was a transcription error and in fact, the text reads ‘In a thousand gentle arms’.

On 17th October 1983, the Etty Hillesum Foundation was established for the purpose of managing the copyrights of Etty Hillesum's diaries and letters. One of its aims is to achieve a scholarly, complete edition of Etty Hillesum's surviving writings. The editions published until then were selections and, moreover, not transcribed by experts, which had led to errors in the text. In addition, the text lacked annotations. Under the leadership of Klaas A.D. Smelik, a group of young researchers began preliminary work. Specialists in the Dutch language, Gideon Lodders and Rob Tempelaar made a transcription of the complete text and provided codicological notes. For the passages in German, they were assisted by the German language specialist, Beate Giebner. Of the two illegally published letters from Westerbork, an original version was discovered in the bundle of letters that accompanied the diaries. This version was included in the edition of collected works. Etty Hillesum's spelling was maintained, apart from a single typographical error, which is discussed at the end of the book.

The notes and commentary also include corrections made by Etty Hillesum herself and also the comments she later wrote in the margins. Accompanying the edition were one hundred pages of annotations written by Klaas A.D. Smelik based on research conducted by the team. In addition to the three researchers already mentioned, Wally de Lang, Els Lagrou, Duke Meijman and Jan Willem Regenhardt also contributed to this volume. The annotations include information about individuals mentioned in the diaries, about historical events referred to in the text, about the quotations from other authors cited, and about books mentioned by Etty Hillesum. The annotations are concise and are intended to facilitate the understanding of the text. The aim was for the collected works to be not only complete and scholarly, but also easy to read.

In 1986 the collected works appeared under the title: ‘Etty: De nagelaten geschriften van Etty Hillesum’. The research did not stop there. In each subsequent edition, changes were made to the annotations and occasionally also to the text. New letters by Etty Hillesum have since surfaced and these have been included as appendices in the latest editions of the collected works. In 2012, the sixth edition was published under a new title: 'The Works' and in 2021 appeared again under the new title: 'The Collected Works'.

The Etty Hillesum Research Center has developed a digital version of the writings it has received by bequest and made it available for scholarly research. In addition, a bilingual edition with original text on the left page and English translation plus footnotes on the right page, was published in 2014 in two volumes by Shaker Verlag. The above text is by Klaas Smelik

(Tekst, Klaas Smelik)

Register for our newsletter and stay tuned!

Molenwater 77

4331 SE Middelburg

The Netherlands

info@ettyhillesumhuis.nl